For 333 years, the Spanish colonizers attempted to rule the Moros. In each attempt, the Moros resisted, leaving the colonizers with no choice but to retreat to their temporary forts. The Tausug Moros of the Sulu Sultanate played a great role in this resistance.

The Tausug Resistance

The people of the Sulu Archipelago embraced Islam around the 13th century. When the Spanish colonizers arrived two centuries later, Islam had already taken deep root in their way of life.

There’s a Kissa or Tausug narrative folk song that says:

“Bang sabab sin sayrulla, pangaku kaw magmula” (“If it is because of cedula, think that you would die.”)

This reflects their rejection of replacing their religion with anything else, as imposed by the Spaniards.

As a group, the Tausug Moros were good maritime soldiers. When they learned of a Spanish royal decree ordering the destruction of their communities, they did not just wait for enemies to come; they went to their homes and struck them first.

The Royal Decree

Around 1851, the Spanish Crown promised its imprisoned convicts a better life. They offered the criminals an unconditional pardon if they went to war against the Moros.

If they could burn their properties, destroy their farms and crops, they would have four-fifths of everything they could collect.

It was a win-win for them. So thousands of prisoners enlisted.

When the Moros heard this, they didn’t just wait for the enemies to reach their land. They sailed to Luzon and the Visayas, carrying out retaliatory raids against Spanish-controlled settlements.

As a Tausug saying goes:

“Mayayao pa muti in bukug ayaw in tikud-tikud” (It’s better to see the whiteness of your bones due to wounds than whiten your heel from running away.

The Spanish-Moro War was actually on and off. And it’s just amazing how the Spanish attempted to rule the Moros with more advanced weapons for over three non-consecutive centuries and still failed to colonize them.

Because when the Tausug could no longer show resistance as a group, they did it individually.

The Emergence of Juramentados

Around the 1870s, the Spanish colonizers sent another fleet to Sulu.

News spread through towns. They did not have social media or newspapers like we do today but every Friday, they gathered to pray and the imam would mention what’s been happening around the town during Khutbah, or Friday sermon. Sometimes, the imam would also mention Jihad, and the reward of dying fīsabilillah (for the sake of Allāh).

And every Khutbah, the young Tausug Moros got motivated to fight for their honor, martabbat.

So the young men asked for their parents’ permission to allow them to fight in the way of Allāh or Parang Sabil.

The parents, knowing that the reward of it is paradise, would agree. Because if they were to die, at least, they did so with honor.

The Making of Mag-sabil

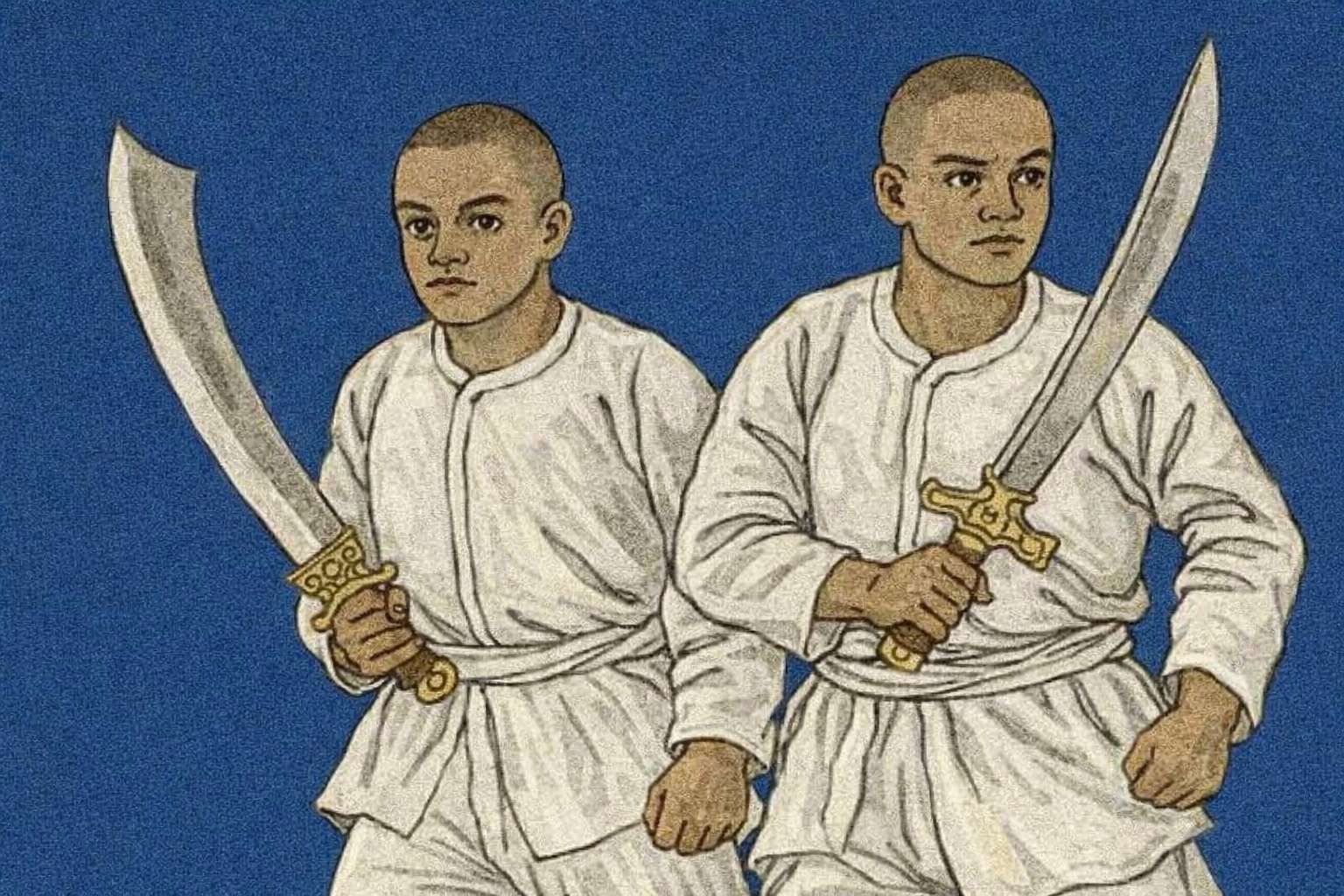

The mag-sabil, the one who wants to die for Allāh, underwent training.

When the day came, he would put his hand on the Quran. He would then perform a bath ritual in the river, facing the four cardinal directions. He would shave all body hair and would trim his eyebrows, resembling the crescent moon. He then wore a white cloth. These are similar rituals done to a corpse.

Bands were wrapped around his waist and cords around his genitals, ankles, knees, upper thighs, wrists, elbows, and shoulders. This prevented him from losing a large amount of blood, allowing him to strike even more, even when injured.

When the day came, the resting Spanish would see a man shouting “La ilaha illallah,” (There is no God but Allāh), swinging his blade, striking to his left and right, killing as many enemies as he could, until his last breath.

This form of individual resistance left a deeper mark on the colonizers’ minds.

By the late 19th century, Spanish officials, including Governor José Malcampo, coined the term juramentados to describe these oath-bound fighters, from the Spanish word “Juramentar”, which means “to swear an oath”.

In some historical writings, these men are described as fanatical. But for the Moros, these are conscious choices in response to the Spanish invasion.

Some historians even use the phrase “running amok”, which most Moro scholars find misleading. Because running amok means the attacker entered a state of trance, unconsciously targeting both Moros and non-Moros. The Tausug mag-sabil, however, was fully conscious and alert. Their targets were precise, and their steps calculated.

This was not similar to the suicide bombings we see in the news today. Whereas modern-day jihadist groups target innocents, Tausug’s Parang Sabil in 19th-century colonial context was shaped by brutal realities of conquest. See full disclaimer.